At the recent Milan fashion show for Dolce & Gabbana, editors of long-established industry bibles like Vogue found themselves relegated to the second row. Most of the young people on the sought-after seats in front of them didn’t work for major media brands or established fashion magazines; instead their influence comes from the number of people following them online. They were there because Dolce & Gabbana’s key audiences have decided they are a more relevant source of style ideas and inspiration.

Those in charge of the seating arrangements at fashion shows aren’t the only marketers reacting to this fundamental change in where influence comes from. If brands are to form the right partnerships and influence the right people, it’s vital they understand how the new influence works.

How social media shifted authority

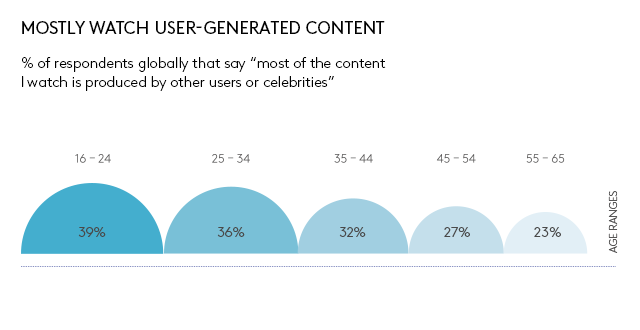

One of the most striking findings in this year’s Connected Life survey from Kantar TNS is the extent to which authority and credibility has shifted. Four out of ten 16 to 24-year-olds say that “most of the content I watch is produced by individuals: either other users/people like me, or celebrities I follow.” And it’s not just the younger generations that have made this switch. In several markets we can see pretty significant consumption of influencer-generated content across the generations.

Those new influencers include the likes of Swedish gaming blogger PewdiePie (the most watched individual on YouTube with 48 million followers) and Wang Sicong, son of China’s richest man, who boasts 21 million followers on Weibo. However, they also include many thousands of less famous influencers, who may specialise in areas as niche as clean eating, hair styling, exercise, or training dogs, and have established large networks of people who regularly consume their content.

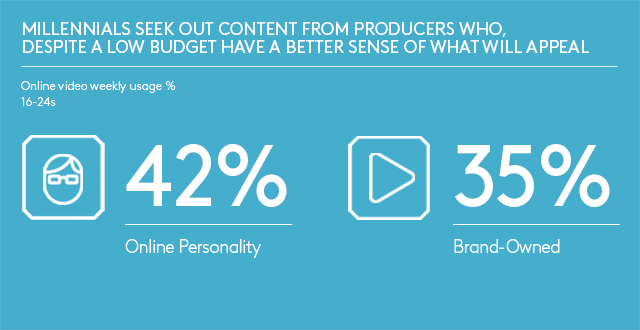

Social media has changed the landscape of influence, with the user-friendly nature of platforms like Instagram and Snapchat lowering the barriers to entry when it comes to producing content that looks and feels credible. Influence depends less on having expensive editorial and technical resources – it resides with those who instinctively understand what makes an audience tick.

Not just new influencers – a new type of influence

Because these individuals are social media celebrities, it’s tempting for brands to use them in traditional celebrity spokesperson roles. This is risky. Because their influence stems from a different form of authority and credibility, it comes with different expectations attached to it.

When YouTube fitness guru Joe Wicks appears in films for Uncle Ben’s rice, he’s offering a traditional style of endorsement – but in reading from an ad agency script, is he sacrificing the authenticity that’s so fundamental to his core appeal? When food blogger Katie Bryson appears in TV ads for Birds Eye, is she doing the same? It’s far from clear whether the values associated with an influencer celebrity can be lent to a brand in the same way that George Clooney’s charisma is borrowed by Nespresso, for example. Influence is less transferable when it comes not from aspiration, but from an audience’s ability to identify personally with an individual.

When Wicks recently launched a content partnership with The Sun newspaper in the UK, and promoted it on Instagram and Facebook, he received hundreds of negative comments from followers who didn’t feel his personal values were compatible with the paper’s politics. Followers feel a strong sense of ownership where influencers are concerned.

Because of this, adapting to the new type of influence isn’t just a case of working with a new cast of characters – it requires marketers to understand a new set of rules too. The brands that succeed will be those that pay close attention to influencers’ relationships with their audiences – and use such insight to inform their own content development.

First, choose the right influencers

It starts with looking beyond simple follower numbers to work out who is generating the most relevant patterns of influence in the most relevant subject areas. The influencers of most value to marketers are often the most specialist, with smaller but more purposeful audiences that are actively seeking expertise and primed to act on it. Marketers need to focus on how relevant an influencer’s followers are, and what they actually do with the content the influencer shares.

Of particular interest is content that generates repeated sharing on the part of an influencer’s network. It’s this sustained, second-wave sharing and commenting that marks out the most effective content on social media.  Influencers are influential because they instinctively understand the emotional triggers that motivate others to get involved – and amplify what they have to say.

Influencers are influential because they instinctively understand the emotional triggers that motivate others to get involved – and amplify what they have to say.

Creative partners, media partners or both?

Analysing and applying those emotional triggers can increase the relevance and engagement for brand content. However, greater authenticity and credibility can come from creating that content in partnership with the influencers themselves. Interestingly, one of the most successful brands in this area doesn’t tend to use celebrity influencers at all. GoPro has built its brand on YouTube and Instagram by encouraging customers to showcase their appetite for the outdoors and extreme sports, their inner creativity – and above all their instinct for producing content that resonates with others like them. The key to its success has been curating an environment that nurtures such grassroots influence – rather than borrowing influence from elsewhere.

When a brand can build a genuinely collaborative relationship with its relevant influencers, it opens up the possibility of using those influencers’ own networks to spread brand content. This is the promised land of influencer-related strategies – a way to tap into relevant audiences that are increasingly difficult to reach through traditional media channels. It’s also the most difficult objective for those strategies to achieve – because influencers’ willingness to put their own credibility at stake depends very much on how genuinely involved they are in content creation. It’s significant, for example, that Joe Wicks’ Uncle Ben’s content appears on Uncle Ben’s YouTube channel rather than his own.

Influencer marketing’s promised land

Evidence is growing though, that brands which focus on creative collaboration can find ways to tap into the reach that influencer networks provide. The travel vlogger Casey Neistat decided to film his upgrade experience on an Emirates flight (sharing with his 5 million YouTube followers and generating over 24 million views on the platform), not because he was paid to do so – but because it was a story he knew would get people excited.

There are millions of potential influencers that can make a relevant contribution to marketing objectives – but this can only be achieved when their influence is understood, respected and applied in a relevant way. If marketers want help winning friends and influencing people, they need to study those doing the influencing as carefully as those they intend to influence.