What do effective social media campaigns look like? Marketers tend to answer this question by adding up numbers. They keep score of views, likes and shares, of the number of feeds that their activity appears in and the number of actions that it prompts. In doing so they can report on the additional reach that social media generates, they can claim engagement with their brand’s message and content, and they can report their progress towards the ultimate prize that such metrics show: going viral.

What if we were to tell you though, that going viral is not enough; that the simple volume of social media activity cannot tell you whether your communications are delivering the objectives that you have almost certainly set for them? What if we were to tell you, in fact, that  meaningful engagement on social media isn’t a numbers game?

meaningful engagement on social media isn’t a numbers game?

The end of the attention economy

The metrics that we gravitate towards for social media effectiveness record a campaign’s success in reaching eyeballs and capturing topline attention. They are easily measurable and appear to make it easy to determine winners and losers: the fact that Mountain Dew’s PuppyMonkeyBaby Super Bowl ad was shared 45,572 times in a week means that it was a success, right? It was almost four times as successful as Heinz’s ‘Wiener Stampede’, which only got 12,341.

The problem for brands is that the crowded nature of social media feeds is devaluing attention as a currency, and undermining the meaning of such metrics. Noticing something momentarily, even clicking it or passing it on as a retweet, does not equate to engagement on the level that brand campaigns need.

We are no longer operating in an attention economy – we need to learn to compete in a memory economy instead. As it happens, our analysis of Super Bowl ads showed that Heinz’s was far more meaningfully memorable than Mountain Dew’s.

We are no longer operating in an attention economy – we need to learn to compete in a memory economy instead. As it happens, our analysis of Super Bowl ads showed that Heinz’s was far more meaningfully memorable than Mountain Dew’s.

For a campaign to deliver long-term brand impact, it needs to change the memory structures associated with a brand in a way that is likely to influence future purchase choices. Retweeting and sharing occurs so frequently and increasingly habitually that it doesn’t correlate meaningfully with whether somebody remembers an encounter with a brand or is influenced by it. Making influential memories depends on a deeper level of engagement – and to understand and influence whether that happens, we need to look at social media differently.

For a campaign to deliver long-term brand impact, it needs to change the memory structures associated with a brand in a way that is likely to influence future purchase choices. Retweeting and sharing occurs so frequently and increasingly habitually that it doesn’t correlate meaningfully with whether somebody remembers an encounter with a brand or is influenced by it. Making influential memories depends on a deeper level of engagement – and to understand and influence whether that happens, we need to look at social media differently.

Social media effectiveness depends on making brand memories

We can assess whether advertising is creating these powerful, motivating memories by looking at three gateways that information must pass through before being encoded into human memory. To make it into memory, neuroscience tells us, any communication must be novel, capturing attention and alerting the brain that it’s worth rewriting its memory structures around; it must have what we term ‘affective impact’, releasing the emotions that strengthen memory formation in the brain; and it must be relevant, aligning with the memory structures that already exist around the brand – and around what matters to people. Looking at whether campaigns pass these three tests predicts whether they will deliver the long-term benefits that brands want from their investments. Researchers can do this by asking the right questions in surveys of advertising effectiveness. However, we can do something very similar by looking at social media data; focusing less on the volume of impressions, likes or retweets, and more on the shape of the conversations that campaigns create.

The shape of memory-making campaigns

Mapping the Twitter activity that occurs around marketing campaigns produces visuals that are intriguing and beautiful – but they are also, increasingly, valuable. The consistent patterns that regularly occur around brand advertising correlate in interesting ways with the success those ads have in forming influential, long-term memories.

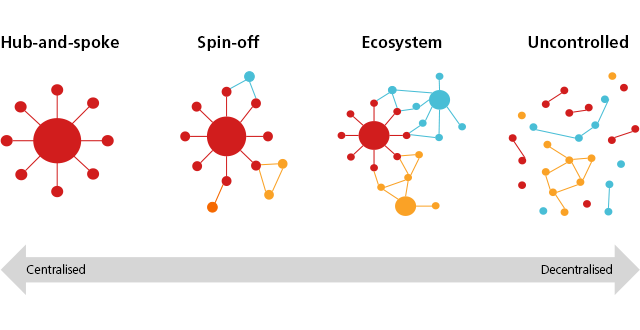

The recognisable conversation patterns that we see can be arranged on a continuum from highly centralised ‘hub and spoke’ models, where all of the social media activity is driven by a central brand account, to highly decentralised ‘uncontrolled’ maps, where many spontaneous conversations occur simultaneously without ever connecting to one another. The sweet spot for brands lies towards the centre of this continuum, where we see autonomous, spin-off networks augmenting the hub-and-spoke pattern, and ecosystems of different groups and communities holding meaningful conversations around the brand.

Budweiser’s hollow Super Bowl win

Budweiser’s hollow Super Bowl win

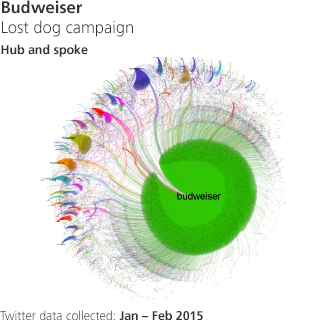

In this way, the shape of social media conversations provides an early warning as to whether a campaign is delivering long-term brand benefits. Back in January 2015, Budweiser was almost universally acclaimed as having ‘won’ the battle of Super Bowl advertising thanks to its heartstring-tugging ‘Lost Puppy’ ad that showed a Labrador pup on an epic journey back to a farm. TNS was a dissenting voice. We knew from our surveys at the time that although the ad was novel and had affective impact, it fell down badly on relevance to the brand and to people’s lives. We knew that Lost Puppy wouldn’t deliver meaningful benefits for Budweiser – and later that year, that’s what Budweiser’s VP Marketing for the US, Jorn Socquet acknowledged that it had failed actually to influence consumer behaviour in any meaningful way: “those ads I won’t air again, because they don’t sell beer.”

Had Soquet had access to maps of the Twitter conversations his campaign was generating, he would have had earlier warning that it wasn't connecting in the way that he would have liked. The ad generated a high volume of activity, reflecting the initial excitement and emotional impact, but this activity added up to little more than an ‘echo chamber’, with people simply retweeting the promotional tweets from Budweiser’s official account. A lack of autonomous conversations showed that communities weren’t taking ownership of the brand activity – they couldn’t talk about it autonomously because it had no obvious relevance to them.

Had Soquet had access to maps of the Twitter conversations his campaign was generating, he would have had earlier warning that it wasn't connecting in the way that he would have liked. The ad generated a high volume of activity, reflecting the initial excitement and emotional impact, but this activity added up to little more than an ‘echo chamber’, with people simply retweeting the promotional tweets from Budweiser’s official account. A lack of autonomous conversations showed that communities weren’t taking ownership of the brand activity – they couldn’t talk about it autonomously because it had no obvious relevance to them.

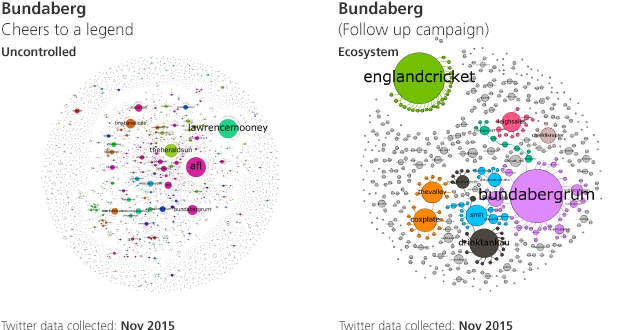

When Bundaberg Rum designed its ‘Cheers to a Legend’ multi-platform campaign it hoped to inspire social media buzz at scale by associating itself with famous sportsmen. It failed to do so – and the Twitter network maps again tell the story. Bundaberg Rum generated a series of unrelated tweets and small-scale conversations that were unconnected both to the brand and to one another. Like Budweiser, the campaign had failed to establish relevance – the difference was that it hadn’t succeeded in establishing much initial excitement either. Small conversations sparked spontaneously into life but never built up any serious momentum to suggest they resonated with online communities.

The pattern of success on social

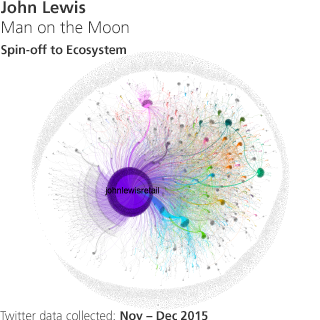

Studying the shape of social media campaigns doesn’t just deliver bad news; it can also show when activity connects on a deeper level than might immediately be apparent. Many UK commentators had concluded that the 2015 ‘Man on the Moon’ Christmas campaign from retailer John Lewis, which focused on the challenging theme of elderly people feeling isolated at Christmas, had missed the mark. Our study of social media conversations shows that it didn’t. The campaign created an ecosystem of automomous Twitter conversations that demonstrate how the issue resonates with people. The fact that those conversations link seamlessly back to John Lewis’s Twitter presence suggests that audiences also saw the subject as relevant to John Lewis’s role as a retailer bringing families together. In contrast, Sainsbury’s ad featuring the beloved childrens’ book character Mog, which seen by many as the winner of Christmas 2015, generated only the same ‘hub and spoke’ pattern that Budweiser’s Lost Puppy had. Relevance to people’s lives was again the missing ingredient.

Studying the shape of social media campaigns doesn’t just deliver bad news; it can also show when activity connects on a deeper level than might immediately be apparent. Many UK commentators had concluded that the 2015 ‘Man on the Moon’ Christmas campaign from retailer John Lewis, which focused on the challenging theme of elderly people feeling isolated at Christmas, had missed the mark. Our study of social media conversations shows that it didn’t. The campaign created an ecosystem of automomous Twitter conversations that demonstrate how the issue resonates with people. The fact that those conversations link seamlessly back to John Lewis’s Twitter presence suggests that audiences also saw the subject as relevant to John Lewis’s role as a retailer bringing families together. In contrast, Sainsbury’s ad featuring the beloved childrens’ book character Mog, which seen by many as the winner of Christmas 2015, generated only the same ‘hub and spoke’ pattern that Budweiser’s Lost Puppy had. Relevance to people’s lives was again the missing ingredient.

This isn’t to say that the volume of tweets a campaign generates isn’t significant. It’s indicative of initial excitement, awareness and word of mouth, all of which matter. However, simply generating a lot of noise on Twitter is no reliable indicator that a campaign is delivering against long-term brand objectives. Even its awareness benefits are likely to be transitory.  A truly successful campaign needs to combine reach and scale with patterns indicating personal relevance.

A truly successful campaign needs to combine reach and scale with patterns indicating personal relevance.

The shape of better social media strategies

Analysing the shape of social media conversations in this way raises some intriguing issues around marketing strategy.

Meaningful success on social media comes from aligning a brand campaign with the issues that motivate existing social communities. This raises questions about the true effectiveness of strategies such as Influencer marketing, which often delivers scale and reach by spreading brand messages through an influencer’s individual network, but doesn’t generate autonomous conversations that show people taking ownership of the issue.

By mapping the communities and conversations that naturally form in the social media space, marketers can identify the issues that motivate and resonate with their target audiences. Finding meaningful, relevant and authentic roles for their brands regarding these issues is a far more effective starting point for planning campaigns that can connect both on social media and beyond. This is what Bundaberg Rum did in response to the initial lack of excitement around its ‘Cheers to a Legend’ campaign, identifying the sporting communities that it needed to connect with, and planning its approach far more carefully around doing so. Later executions focused on carefully selected sportsmen generated both a greater volume of Twitter conversation – and more genuine engagement with Twitter communities. Influencer marketing has a role to play in such strategies, when it is able to bring out the role and relevance of the brand for the different communities in the Influencer’s network.

Analysing the shape of social media conversations doesn’t just provide a far more meaningful understanding of whether brands are meeting their objectives; it also provides vital guidance as to how they can do so. Looking beyond topline numbers and harnessing the chaos, topology, shape and structure of social media engagement holds the key to going viral in way that truly matters.